New research unveils how Britain clandestinely appropriated the technology to rule the Industrial Revolution

Durrant Pate/Contributor

New research has unearthed that the wrought iron process that propelled Britain to become the world’s leading iron exporter during the Industrial Revolution was apparently stolen from an 18th-century Jamaican foundry.

In fact, the research paper, published in the journal History and Technology says this stolen technology drove Britain’s success during that era, when the real developers, black metallurgists from Jamaica weren’t even recognized or their development of the technology acknowledged.

The Cort process, which allowed wrought iron to be mass-produced from scrap iron for the first time, has long been attributed to the British financier turned ironmaster, Henry Cort. It helped launch Britain as an economic superpower and transformed the face of the country with “iron palaces”, including Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens’ Temperate House and the arches at St Pancras train station.

New research crediting Jamaica

The British Guardian has picked up the story from the research showing that “an analysis of correspondence, shipping records and contemporary newspaper reports reveals the innovation was first developed by 76 black Jamaican metallurgists at an ironworks near Morant Bay, Jamaica. Many of these metalworkers were enslaved people trafficked from west and central Africa, which had thriving iron-working industries at the time.”

Dr Jenny Bulstrode, a lecturer in the History of Science and Technology at University College London (UCL) and author of the paper says the technique was patented by Cort in the 1780s for which he is widely credited as the inventor with the Times lauding him as “father of the iron trade” after his death.

But this latest research by Dr. Bulstrode presents a different narrative, suggesting Cort shipped his machinery and the fully-fledged innovation to Portsmouth from a Jamaican foundry that was forcibly shut down. The research shows that the Jamaican ironworks was owned by a white enslaver, John Reeder, who in correspondence described himself as “quite ignorant” of iron manufacturing, noting that the 76 black metallurgists who ran the foundry were “perfect in every branch of the iron manufactory” and through their skill, could turn scrap and poor-quality metal into valuable wrought iron.

According to the Guardian, some of these workers are named in records and include Devonshire, Mingo, Mingo’s son, Friday, Captain Jack, Matt, George, Jemmy, Jackson, Will, Bob, Guy, Kofi and Kwasi.

Jamaicans innovation in iron manufactory

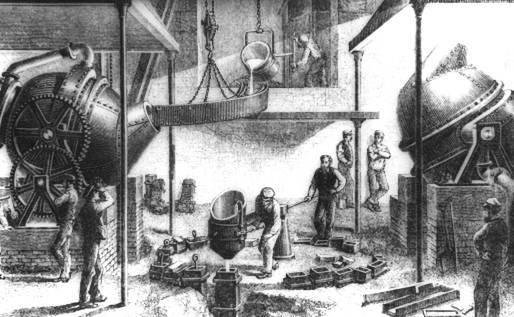

The research paper details that their innovation came after the workers introduced the use of grooved rollers into the foundry to mechanise the formerly laborious process of hammering out impurities from low-quality iron. The same kind of grooved rollers were used in Jamaican sugar mills.

“It’s like a mechanical alchemy,” explains Dr. Bulstrode adding “You’re taking essentially rubbish and turning it into something of very high value through this process.” By 1781, the Jamaican ironworks was turning an impressive profit of £4,000 a year, equivalent to about £7.4 million today.

The research paper traces how Cort, who was facing bankruptcy, after taking over a client’s ironworks in 1775 and laying out substantial sums to win a Royal Navy contract to process its scrap iron, before realising he stood to make a huge loss, learnt of the Jamaican technology.

Scheming to acquire the technology

The research indicates that Cort learnt of the Jamaican ironworks from a visiting cousin, a West Indies ship’s master who regularly transported “prizes” – vessels, cargo and equipment seized through military action from Jamaica to England.

Just months later, the British government placed Jamaica under military law and ordered the ironworks to be destroyed, claiming it could be used by rebels to convert scrap metal into weapons to overthrow colonial rule.

The machinery was acquired by Cort and shipped to Portsmouth, where he patented the innovation. Five years later, Cort was discovered to have embezzled vast sums from navy wages and the patents were confiscated and made public, allowing widespread adoption in British ironworks.

Dr Bulstrode hopes to challenge existing narratives of innovation. According to her, “If you ask people about the model of an innovator, they think of Elon Musk or some old white guy in a lab coat. They don’t think of black people, enslaved, in Jamaica in the 18th century.”

Dr. Sheray Warmington, an honorary research associate at UCL says the work is important for the reparations movement. She comments, “It allows for the proper documentation of the true genesis of science and technological advancement and provides a starting point for how to quantify and repair the impact that this loss has had on the developmental opportunities of postcolonial states, and push forward the discourse of technology transfer as a key tenet of the reparations movement.”

Comments