(Reuters)

The more weight people with type 2 diabetes lose, the greater the odds that the disease will go partially or even completely into remission, according to a new analysis published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Reviewing 22 earlier randomized trials testing weight loss interventions in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes, researchers found complete remission of the disease in half of those who lost 20% to 29% of their body weight. Nearly 80% of patients who lost 30% of body weight no longer appeared to have diabetes.

That means their hemoglobin A1c levels – a standard measure reflecting average blood sugar levels over the past few months – or their fasting blood sugar levels had returned to normal without use of any diabetes medications.

No one who lost less than 20% of their body weight achieved a complete remission, but some were in partial remission, with hemoglobin A1c and fasting glucose levels returning almost to normal.

Partial remission was seen in roughly 5% of those who lost less than 10% of their body weight, and that percentage rose steadily with greater weight loss, reaching nearly 90% among those who lost at least 30%.

Overall, for every 1 percentage point decrease in body weight, the probability of reaching complete remission increased by roughly 2 percentage points and the probability of reaching partial remission increased by roughly 3 percentage points, regardless of age, sex, race, diabetes duration, blood sugar control, or type of weight loss intervention.

Type 2 diabetes accounts for 96% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes, and more than 85% of adults with the disease are overweight or obese, the researchers noted.

“The recent development of effective weight loss medications, if made accessible to all who could benefit, could play a pivotal role” in reducing the prevalence of diabetes and its complications, the researchers said.

New bone marrow transplant method may cure sickle cell disease

A new bone marrow transplant method can help cure sickle cell disease and is more accessible than highly expensive gene therapies for the disease, researchers say.

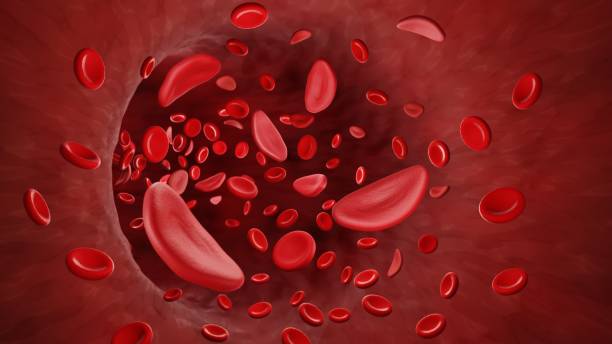

Sickle cell disease is a genetic blood disorder, primarily occurring in Black individuals, that changes the shape and function of red blood cells, leading to severe pain, organ damage, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality.

The new transplant procedure, already available at multiple medical centers, is less costly than recently approved gene therapies for sickle cell disease, researchers reported in two separate papers.

Among 42 young adults with severe sickle cell disease who underwent the procedure, called reduced intensity haploidentical bone marrow transplantation, 95% were alive two years later and 88% were considered cured and experienced no disease-related events, according to a report published in The New England Journal of Medicine Evidence.

“Our results… are every bit as good or better than what you see with gene therapy,” study coauthor Dr. Richard Jones of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine said in a statement.

Unlike traditional bone marrow transplants, the new method does not require marrow from a specifically matched donor to avoid triggering an immune response.

That difference makes it much easier to find an appropriate marrow donor.

“A common misconception in the medical field is that transplantation for sickle cell disease requires a perfect matched donor… which this trial and other studies have shown aren’t true,” coauthor Dr. Robert Brodsky, also of Johns Hopkins, said in a statement.

Before the transplant, patients received low doses of chemotherapy and total body irradiation. Afterward, they were treated for one year with chemotherapy to prevent the donor’s immune cells from attacking the recipient’s body.

In a separate paper published in Blood Advances, the research team estimated that new gene therapies for sickle cell disease cost $2 million to $3 million, compared to less than $500,000 for a bone marrow transplant.

Furthermore, hospitalizations for bone marrow transplants average about eight days, as opposed to six-to-eight weeks for gene therapy, Brodsky said.

While many with sickle cell disease have organ damage that would make them ineligible for the high-dose chemotherapy required with gene therapy, most would be eligible for the transplant, Jones said.

Comments