The Andrew Holness-led Government is being urged to do more at the local level to help Jamaica’s coral reefs survive climate change.

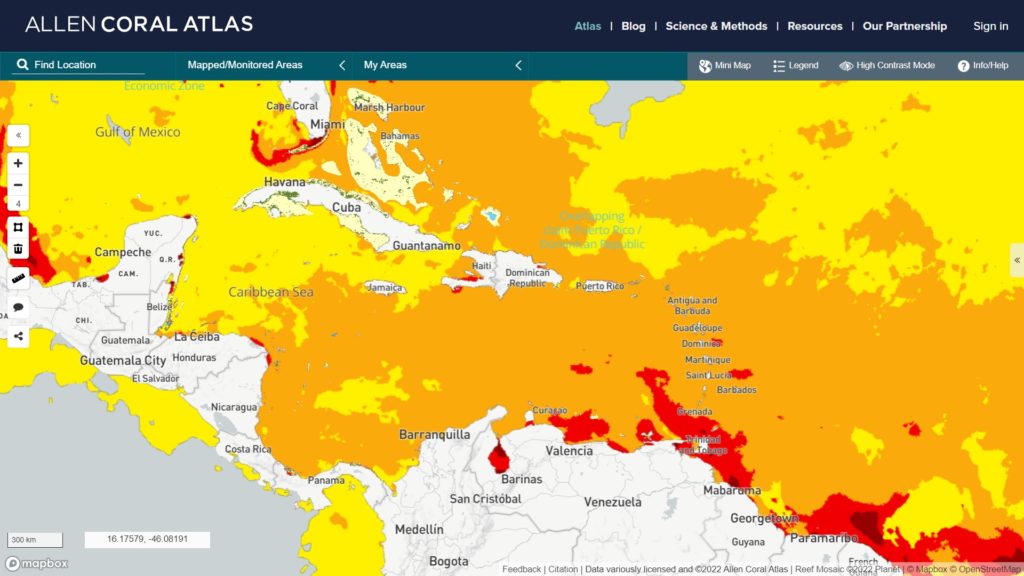

The call comes as the Arizona-based Allen Coral Atlas warns that rising surface temperatures across the Caribbean Sea are fuelling a coral bleaching phenomenon sweeping the entire region, which is only likely to worsen amid a devolving, uncertain climatic future.

The atlas, an operational product of the Arizona State University (ASU) since 2020, shows that Jamaica is under consistently moderate coral bleaching as of January 31, 2022.

Negative impacts of coral bleaching are more pronounced along Jamaica’s south coast—particularly at the southeastern tip of Clarendon along its shared border with St Catherine—while the issue affects a large majority of the local reef network.

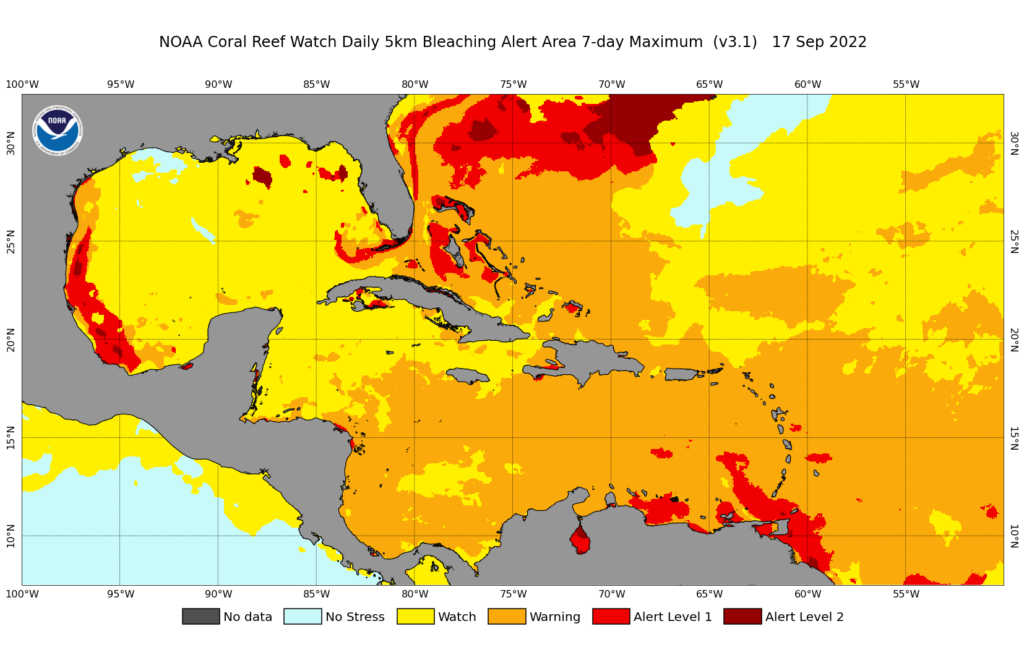

As recently as September 17, 2022, a Coral Reef Watch managed by the US-based National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), has placed the “current stress level” of coastal waters around Jamaica including its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) at a “bleaching warning”.

The island was upgraded from a “bleaching watch” in February this year and has been undulating between watch and warning for most of Summer 2022.

NOAA’s data, which the Allen Coral Atlas also utilises in its monitoring of at-risk areas, suggest the level has remained consistent for the last eight years since 2014.

Since October 2015, NOAA’s standard four-month bleaching outlook indicated that the threat of bleaching has continued in the Caribbean, Hawaii and Kiribati, potentially expanding into the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

For the rest of the region, however, coral bleaching is worryingly high and has risen to crisis levels in Bermuda, central and northern Bahamas, northwest and southwest Cuba, southern Hispaniola, Trinidad and Tobago, nearshore and offshore Venezuela, and the Dutch Caribbean islands of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao as well as Panama’s western Atlantic coast.

See breakdown of coral bleaching levels across the Caribbean, as reported by NOAA data below:

| Country/Territory/Region | Current coral stress level (as at September 17, 2022) |

| Bermuda | Bleaching Alert Level 2 |

| Central Bahamas Northern Bahamas | Bleaching Alert Level 1 Bleaching Alert Level 2 |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | Bleaching Warning |

| Northwestern Cuba Northeastern Cuba Southwestern Cuba Southeastern Cuba | Bleaching Alert Level 1 Bleaching Warning Bleaching Alert Level 1 Bleaching Warning |

| Cayman Islands | Bleaching Watch |

| Jamaica | Bleaching Warning |

| Northern Hispaniola Southern Hispaniola | Bleaching Warning Bleaching Alert Level 1 |

| Puerto Rico | Bleaching Warning |

| Virgin Islands | Bleaching Warning |

| Leeward Caribbean | Bleaching Warning |

| Windward Caribbean | Bleaching Warning |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Bleaching Alert Level 1 |

| Nearshore Venezuela Offshore Venezuela | Bleaching Alert Level 1 Bleaching Alert Level 1 |

| Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao | Bleaching Alert Level 1 |

| Belize | Bleaching Warning |

Speaking exclusively with Our Today, coral reef biologist Brianna Bambic, lead of the Allen Coral Atlas‘ field engagement team, and respected marine biologist, Dr Andrea Rivera Sosa, hope that the atlas, through the data presented, will underscore to governments and the wider public the importance of coral reefs and their inextricable link to human survival.

Utilising high-resolution satellite imagery and advanced analytics to map and monitor the world’s coral reefs in unprecedented detail, the Allen Coral Atlas covers a general two-year period from 2018 to 2020.

According to Bambic, the coral benthic and habitat maps are based on a combination of underwater and aerial images from 2018-2020, which also provide a region-by-region breakdown. A quarterly turbidity dynamic monitoring is available on the atlas starting in the fourth quarter of 2019 (covering October-December), while the bleaching dynamic biweekly monitoring is also accessible starting from January 2021.

“For 2021, starting on October 11th, the Atlas shows patchy ‘low’ bleaching occurring in <10 km stretches along the northwest coast. This bleaching event intensifies and expands to cover >75 km of the northeast coast of Jamaica and further to the south and southwest reefs, with some areas escalating to ‘moderate’ bleaching levels. This 2021 bleaching event was ‘low-to-moderate’ but continued throughout October [and] November until Dec 20th when the atlas data reported the bleaching stopped or the colour of the coral came back or potentially algae overtook the coral. Our satellite-based technology does not report on recovery of coral, yet,” Bambic explained.

In the eyes of the team, coral bleaching is defined as environmental stresses placed on a reef system, a living, ‘breathing’ organism, due to increases in sea temperature that causes the corals to lose colour (bleach), turn white and struggle to photosynthesize.

The phenomenon does happen naturally but is now exacerbated by human-induced global warming, which has seen oceanic temperatures incrementally rising and remaining at warmer-than-usual levels over the last decade.

“Coral stress comes from either water that is too hot or contaminated. In these conditions, bleaching will persist. Optimistically, if the water cools or contamination in water is cleaned up and a healthy fish population is present to eat the algae that can grow over the bleached coral within two weeks – if all these things go right, the corals can live again,” Bambic noted.

A dying reef system makes the possibility of climate adaptation and mitigation much harder for small island developing states (SIDS) like Jamaica, as countries become exposed when the wave energy-absorption benefit coral reefs provide is lost.

“Half of the world’s coral reefs have died over the past 50 years due to climate change and other stressors. Models predict the loss of between 70 and 90 per cent of coral reefs by 2050 at the current rate of loss. What we know is that this is a global issue that needs to be acted upon locally, regionally and globally to change the pace of coral bleaching,” she told Our Today.

“A recent study estimated the increase in storm damage resulting from loss of one metre off the top of the world’s reefs at US$4 billion annually. Reefs reduce up to 97 per cent of wave energy that would otherwise hit coastlines, averting tens to hundreds of millions of dollars in flood damage every year,” the coral reef biologist added.

The two experts indicated that much more is at stake since at least 25 per cent of marine species depend on coral reefs at some point in their life cycle.

From an economic standpoint, the losses are staggering. They could fall in the range of US$2.7 trillion to the economies of 50 nations, as more than one billion people depend on reefs for food, storm protection, and tourism income.

Without healthy coral reefs, the world faces the risk of significant marine species decline and major disruption of coastal communities, some of which have already begun in sections of the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

“This can be done by the decrease of stressors such as overfishing and wastewater. Solutions such as safeguarding fishing grounds for juvenile fish can ensure future fisheries. Also, proper sewage treatment plants need to be enforced to enhance water quality that will allow coral reef ecosystems to stay healthy. By tackling global and local stressors, we will be able to safeguard local ecosystems,” Bambic said.

Comments