By Zoe Clarke

Non-compete clauses are restrictive legal agreements designed to prevent employees and parties, particularly those who are talented and productive from moving on expeditiously to take up other employment opportunities.

It is a protective measure that can keep carriers in stasis and prevent them from taking opportunities. The fear is the exiting worker will divulge company secrets.

Non-compete clauses have become a mainstay of employment contracts for decades but recently the United States’ Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has taken a more equitable approach, seeking to protect the fundamental freedom of workers to opt for other jobs.

“Non-compete clauses keep wages low, suppress new ideas and rob the American economy of dynamism including from the more than 8,500 new start-ups that would be created a year once noncompetes are banned. The FTC’s final rule to ban non-competes will ensure Americans have the freedom to pursue a new job start a new business, or bring a new idea to market,” said FTC Chair Lina M Khan.

Here Zoe Clarke examines the ramifications of the FTC’s ban on non-compete clauses and what it will mean for American workers and alternative restrictive covenants.

The recent Federal Trade Commission (FTC) rule, which retroactively bans non-compete clauses, represents a significant shift in employment law with wide-reaching implications for alternative restrictive covenants.

The new rule aims to enhance worker mobility and innovation by explicitly prohibiting non-compete agreements, which have been widely criticized for suppressing wages and limiting competition.

The FTC predicts that the final rule will eventually lead to a proliferation of new businesses and higher employee wages. Non-compete agreements are incredibly prevalent and often exploit workers by imposing unreasonable restrictions that hinder their ability to find new employment or start their own businesses.

These non-compete clauses can effectively trap an employee in unwanted jobs or force them to endure significant hardships, such as transitioning to lower-paying careers, relocating, leaving the job market entirely, or juggling expensive legal disputes. The final rule, however, does carve out an exception that allows certain current non-compete agreements with senior-leveled executives earning a specified annual salary to remain valid.

The final rule presents various significant concerns, such as its enforceability, potential legal disputes, policy ramifications, and interplay with current existing laws. Almost immediately, backlash and resistance opposing the ban on non-compete clauses surfaced just shortly after the FTC announced the ruling.

On April 24th, 2024, just one day after the FTC’s ruling, the US Chamber of Commerce, along with various other business organizations, filed a lawsuit against the FTC in a federal court in Texas.

This legal action challenges the FTC’s recent decision to prohibit non-compete clauses, which are known to prevent employees from moving to competitors within the same industry. Challengers of the ban argue that the FTC lacks the legal authority to enforce such a ban and that the scope of the rule is excessively broad.

Additionally, the FTC rule supersedes state laws that permit non-compete agreements but does not preempt state laws offering even greater protection to workers. This federal-state law interplay may result in varied enforcement and compliance challenges across different states, potentially complicating the implementation process.

This significant regulatory change has far-reaching implications for employers and employees alike, particularly regarding alternative restrictive covenants such as garden leave, non-disclosure, and non-solicitation agreements.

Broadly speaking, a garden leave agreement requires an employee to stay away from work during their notice period while still being paid, which is commonly used to ensure that employees do not take any sensitive information or company secrets with them as they transition out of their current role.

On the other hand, non-disclosure agreements are designed to restrict the sharing of confidential or proprietary information with competitors or other interested parties. Non-solicitation agreements prevent employees from recruiting coworkers to join a competitor and from persuading customers or vendors to shift their business to a competing company, which is crucial for protecting business relationships and maintaining workforce stability after an employee departs. Restrictive covenants, such as non-disclosure agreements, allow businesses and employers to safeguard the investments that they make in employees despite not being allowed to enforce a non-compete clause.

FTC commissioners in a closely contested 3-2 vote along party lines, approved a highly anticipated rule that largely bans employers from implementing or enforcing non-compete clauses with American workers, except in limited circumstances under the exception.

The final rule will take effect 120 days (about 4 months) after its publication in the Federal Register, the official government publication, where rules and decisions are announced. It was published in the Federal Register with an effective date of September 4, 2024, which marks the date when this new rule will officially start being used and enforced across the country.

Why the Ban?

On April 23rd, 2024, the FTC issued a final rule which was implemented with the hopes of boosting competition by federally banning non-compete clauses, which aims to protect the autonomy of employees to be able to change jobs and promotes the creation of new businesses.

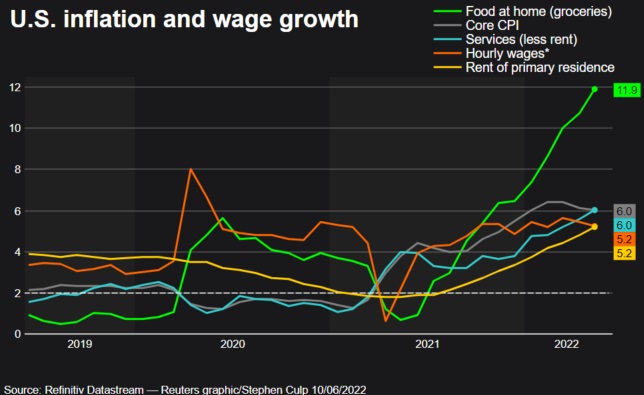

The FTC determined that non-compete agreements unlawfully hinder competition and suppress wages for American workers. The FTC suggested that eliminating these agreements would promote competition, spur innovation, and lead to higher wages. Additionally, in 2021, the current administration issued an executive order instructing the FTC to restrict non-competes, revealing that this regulation has been in development for some time.

When employees are unrestricted in their ability to change jobs within an industry, they are encouraged to enhance their human capital and cultivate their skills. Non-compete agreements diminish employee drive, innovation, and the exchange of knowledge, which are crucial components of fostering creativity. When employers are unable to limit workers through non-compete agreements, new incentives emerge as substitutes for restrictive measures: employers adopt increased use of performance-based rewards, proactive retention strategies, and stock options to retain top talent. Collectively, these dynamics contribute to fostering a more productive, competitive, and innovative environment.

In the past, noncompete clauses have restricted low-wage workers from changing jobs which resulted in limited career advancement and suppressed overall wage growth, as noted by the FTC. This lack of mobility has stifled competition and kept earnings low across various sectors. The FTC’s new proposal seeks to dismantle these barriers, enabling employees, particularly those in low-income positions, to pursue better opportunities or even launch their own ventures. This change is expected to boost wages and foster a more competitive job market.

The ban prohibits all future non-compete clauses and retroactively bans pre-existing non-compete clauses with an exception. The FTC predicts that implementing the final rule to ban non-compete agreements will spur a 2.7% annual rise in new business formations, potentially leading to the establishment of over 8,500 new businesses each year. This regulation is also expected to boost average worker earnings by an additional $524 annually. Moreover, it could result in a reduction of healthcare costs by as much as $194 billion (about $600 per person in the US) over the next decade. The rule is also likely to drive innovation, with projections indicating an increase of 17,000 to 29,000 new patents each year for the next ten years.

Exception to the Ban

The FTC final rule exempts specific industries from its provisions. Exclusions apply to banks, savings and loan institutions, federal credit unions, common carriers, air carriers, and foreign air carriers, and entities governed by the Packers and Stockyards Act. Other notable exceptions encompass (1) current agreements pertaining to “senior executives”, (2) non-compete agreements formed during bona fide business sales, and (3) non-compete agreements enforced for actions occurring before the rule’s effective date.

For existing non-compete agreements, the rule takes a stance based on employee status. The regulation applies universally to all individuals engaged in work, extending beyond those classified as W-2 employees. Within the framework of this regulation, the definition of “worker” is expansive, including any individual who has performed or previously performed services for another person. This includes employees, independent contractors, interns, volunteers, apprentices, sole proprietors, minority owners, and any other natural persons offering their services.

The span of this definition ensures that the regulation encompasses a diverse array of work arrangements and employment statuses. However, senior-level executives are permitted to retain their existing non-compete agreements, whereas such agreements with other employees will be invalidated once the rule is in effect.

It is anticipated that fewer than 1% of workers will fall under the category of senior-level executives as defined by this rule. The final rule defines “senior executive” as an employee earning more than US$151,164 in annual compensation during the previous year and holding a position with policy-making responsibilities.

Under the final rule, a senior executive’s “total annual compensation” may consist of salary, commissions, non-discretionary bonuses, and other non-discretionary earnings from the preceding year, excluding the cost of or contributions to fringe benefit programs.

The final rule further specifies that individuals in policy-making positions include 1) the organization’s President, 2) the CEO or equivalent, or 3) other individuals with “policy-making authority”. Accordingly, non-compete agreements currently in effect for these individuals can continue without alteration, and there is no requirement for employers to notify these senior-level executives of the ban.

Zoe Clarke is a Law student at the Nova Southeastern University in Florida, the United States.

Comments