Over the last twenty years, dozens of programs to prevent crime and violence have emerged. None of them seem to be working. We still have the highest murder rate in the world.

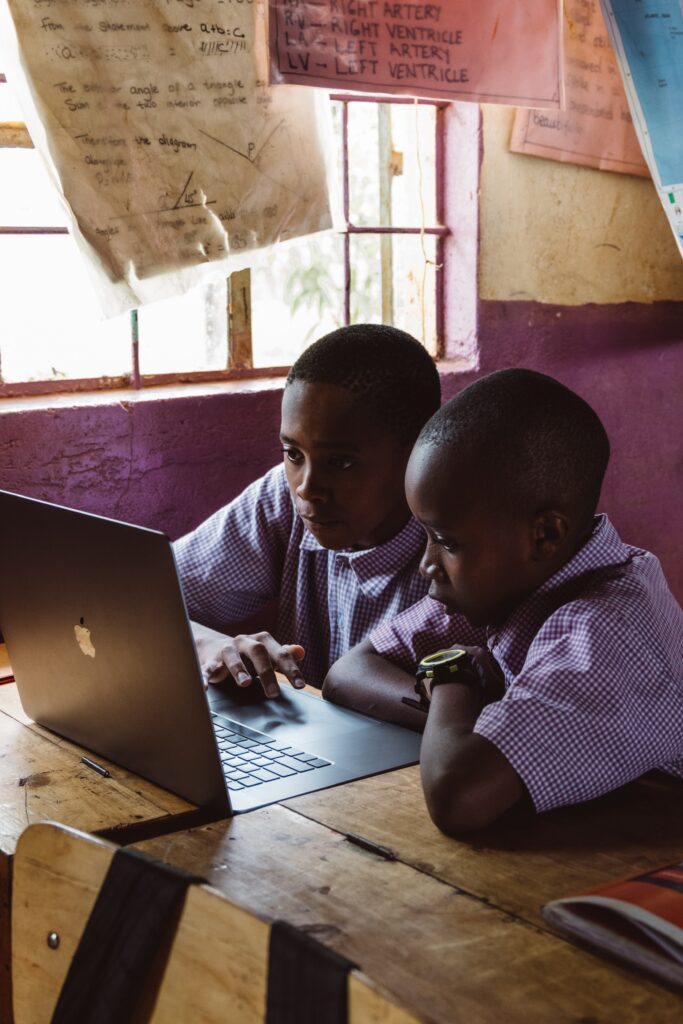

Millions have been spent to build new schools and repair old ones. But, our literacy rate has only seen a marginal increase of less than one percent over eight years.

Despite the emergence of new entrepreneurial grant funding, easing of business registration, increased access to loans, and innovative training programs, Jamaica’s national productivity rate continues to decline while the rest of the Caribbean climbs.

What are we doing wrong?

We tend not to define specific goals with realistic timelines. An example of a properly formulated goal would be – decrease crime by 30% in 5 years. Our goals need to be understood by all stakeholders as well as made known to the beneficiary communities and the general public.

We do not define success indicators so that we can track progress throughout the project. An early sign of success for a nutrition program for primary schools would be a 5% decrease in absenteeism across schools in 1 year. The children are being fed at school so they come to school for both their education and nourishment- they are less likely to miss school.

A long-term sign that the program is working would be a 15% increase in graduation rates in primary schools over 10 years. These performance indicators should be defined before we begin the program.

When we don’t see results, we keep doing the same old thing without going back to the drawing board and trying something new. Six months in, 1 year in, and 3 years into a violence prevention program and violence is still rampant- clearly, the methodology needs to be rethought.

We need the early success indicators so that we can identify that our program is failing. Quit the ineffective pathways to change, learn from the mistakes, do more of what’s working, and invent anew.

Speaking of learning from mistakes, we do not look back at past national programs. We keep starting over from scratch without building on the learnings from the past. You’d be shocked to find out how many social transformation programs have tackled the same community or national problem over the years. It’s all been done before.

If we were to go back to the 1970s and look at all the programs that were tried, tested and failed- we would learn a lot that could help us now. Literacy initiatives, economic development projects, agriculture programs, and the list goes on and on. And still, every time we start a project, we design something completely new.

We need shared learning across organizations and across time. How can we build the house if we keep knocking it down and starting over?

We have massive national committees with stakeholders from multiple agencies and organizations represented. But without clearly defined roles and responsibilities, the massive committees are ineffective.

Just think about all the committees designed during the pandemic to tackle vaccination, education, and economic decline. They were all massive committees, but the size of their impact did not match the power and size of their team.

Programs need tightly designed and effective committees with relevant members. If Bob isn’t doing his part, it’s time for him to go. Find another member who is sufficiently energized to participate, lead, and be held accountable.

Additionally, bitter rivalries and disagreements between project contributors are no reason for the overall project to peter out.

One of the biggest challenges we face when implementing national programs is that we do not meet the beneficiaries where they are. If we want to instigate change, we have to understand the issues from their perspective and solicit their input.

In the 1940s, there was an island-wide campaign to encourage marriage. This Mass Marriage Movement was created without knowledge of how Jamaican family life is organized. It failed. Its greatest accomplishment lifted the Jamaican marriage rate by less than 1% in two years. After 10 years, the marriage rate went back to its previous levels. Shortly after, the Mass Marriage Movement program died down.

We have to think about the people we wish to serve, their needs, and how they think

If we want taxi operators to obey the traffic rules, we have to recognize the existing frictional relationship between the police and taxi operators and improve their relations before we can see more cooperation and adherence to the laws. That’s what we learned from the successful Public Order Reset Initiative in Montego Bay.

We are quick to reach for press and publicity without any real impact felt on the ground. We have grand launches and press announcements even when nothing has happened yet. We need to start implementing our projects, watching them closely, tweaking the methodology accordingly, and seeing the early results and success indicators before we make a big announcement in the media about our do-good efforts.

Rushing to praise the project before the work is done creates illusions of productivity and leads to distrust, and lack of accountability.

National Pride is a new monthly Our Today column documenting social transformation programs that actually work.

If you have a project or initiative that has yielded tangible results and would like us to profile it, email Joelle Simone Powe at [email protected].

Comments