I write to correct recent suggestions making the rounds that tourism’s contribution to Jamaica’s economy is 6.5 per cent of GDP share and employment of over 113,000 people.

This is in direct contrast to a World Bank report on Jamaica during the COVID-19 pandemic which couldn’t have been clearer on tourism’s status as the lifeblood of the local economy.

The World Bank report on Jamaica during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which started in March 2020, stated, “The pace of Jamaica’s recovery will depend on the global containment of the pandemic and easing of travel restrictions with the rollout of vaccines.”

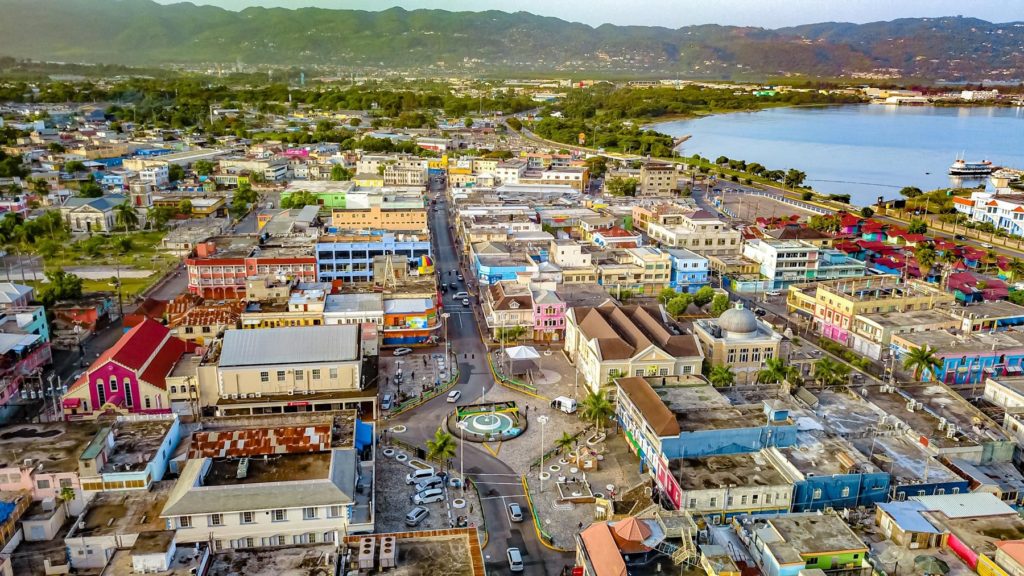

This is important given that the tourism sector contributes over 30 per cent of GDP and supplies a third of the country’s jobs, encompassing both direct and indirect contributions. Furthermore, the 2019 Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) results placed tourism’s direct contribution to GDP at 9.5 per cent, with significant spillover effects across the economy. This contextual discrepancy is crucial to understanding tourism’s true economic impact and its potential as a growth driver.

While acknowledging tourism’s resilience and recovery from challenges such as hurricanes and negative travel advisories, there is an apparent missed opportunity in examining what could be done to further optimise this vital industry.

The retention of only 40 per cent of tourism earnings domestically, as some have been suggesting, raises an important question: Why not more? The fact that Jamaica has an excess capacity of rooms and a proven ability to rebound from shocks suggests immense potential.

There is no better proof of the capacity of the tourism industry to grow the economy than when the sector came to a halt during the pandemic. As someone who had the privilege of representing the Private Sector Organisation of Jamaica (PSOJ) at the time, I witnessed how the Bank of Jamaica (BOJ) incorporated projected tourism recovery into their outlook to estimate the broader economic recovery.

There was in my opinion a direct correlation between tourism recovery and the recovery of specific industries such as agriculture, manufacturing and the wider economy, a fact that should not be lost in the moment.

The question is, If not tourism, then what other sector can we promote that will sustainably grow the Jamaican economy with the speed needed? This example demonstrates the undeniable power of tourism.

Should we not as a country support increasing advertising and airlift seat support spending to strengthen this high-potential industry that can generate short-term inclusive economic growth?

Tourism is not just a cornerstone of the current economy; it is a sector that could deliver significantly more if approached as a national priority. The Ministry of Tourism, under the leadership of Edmund Bartlett, has done a commendable job in expanding the benefits of tourism for Jamaicans.

However, to achieve its full potential—similar to how oil-rich countries like Dubai and the United Arab Emirates are leveraging tourism—it must become a national policy supported by an all-of-government approach.

Tourism foreign direct investments (FDIs), particularly in the development of accommodations, represent an added value that the editorial did not mention. These investments contribute to infrastructure, employment creation, and supplier linkages, all of which benefit local industries and drive long-term economic growth.

Retention of the tourism dollar has improved significantly over the past decade—from a previously estimated 20 per cent to the 40 per cent quoted in the editorial. This improvement has allowed many local suppliers to enjoy a thriving domestic market, free from the shipping costs, tariffs, and barriers often encountered in traditional export markets. This progress must be celebrated, but there is room for so much more.

Conversely, local consumption funded by remittances often involves significant imports, such as food staples (flour, rice, canned goods), clothing, and even energy bills (as JPS imports fuel for operations). While remittances are undeniably valuable, much of this spending benefits foreign economies. This brings us to a critical question: how can we develop stronger linkages for both tourism and local consumption to reduce the outflow of foreign exchange? Are there economies of scale to be realised by analysing consumption holistically and building local supply capacity? And most importantly, is this effort purely a tourism initiative, or does it require a broader, national strategy?

Additionally, the suggestion of tourism’s direct GDP contribution at 6.5 per cent is clearly if not grossly understated. In 2019, when revenues were US$3 billion, tourism contributed an estimated 9.5 per cent to GDP. With 2023 revenues projected at US$4.38 billion, the contribution should be even higher, particularly when factoring in indirect contributions and spillover effects across various sectors. A review of this data is warranted to accurately reflect tourism’s true impact.

The development of human capital is another crucial aspect that deserves emphasis. Jamaica’s commitment to training and upskilling its workforce equips citizens to earn more and participate in high-value sectors of the tourism economy. This focus on human capital ensures that Jamaicans are not only workers in the industry but also active beneficiaries of its growth, further increasing the domestic retention of revenues.

Finally, examining the last 25 years of tourism arrivals and identifying the effects of major shocks reveals an undeniable truth: Jamaica’s tourism industry is exceptionally resilient. Despite natural disasters, global crises, and economic downturns, tourism has consistently rebounded, proving its stability and growth potential.

No other industry offers the same combination of immediate capacity (excess rooms now and growing), a proven and expanding global market, and the potential to increase its economic footprint. Tourism is uniquely positioned to drive inclusive growth by capturing a greater wallet share of visitors through diversified offerings, investment in high-quality local products, and strategies targeting longer stays and higher-spending demographics.

Jamaica’s tourism industry is not just poised to survive but to thrive and lead as an engine of economic growth. The conversation should shift from merely recognising what tourism contributes now to exploring bold strategies for what it could become in the future. With deliberate effort, the retention of tourism earnings could climb well beyond 40 per cent, multiplying its impact on the national economy and creating greater prosperity for all Jamaicans.

Jamaica must embrace tourism not only as it is but as it could be—a catalyst for inclusive and sustainable economic growth. By integrating tourism into a broader national initiative to strengthen domestic supply chains, reduce imports, and enhance local linkages, the industry’s benefits can extend far beyond its current scope.

John Byles is the deputy chairman of the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB).

Comments