If the defence was truly “provocation” and not premeditated behaviour, then serious questions remain — questions that Jamaicans are already asking in homes, workplaces, and communities across the country.

If there was alleged research about how to get away with it, why was no ambulance called? Why were there reports of changes to the home afterwards? Why was a death initially believed to be from natural causes? These are not emotional or sensational questions — they are accountability questions.

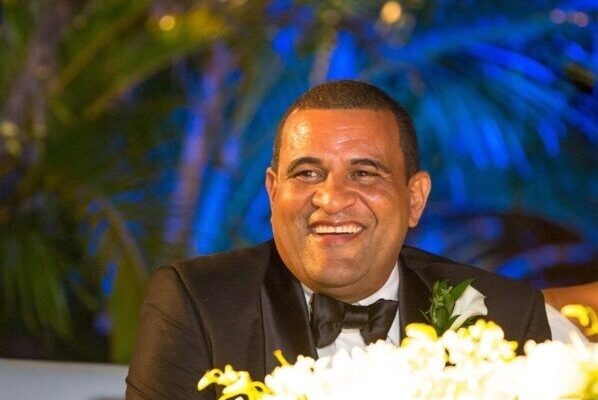

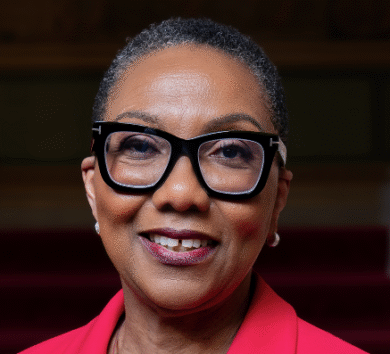

The Silvera case has forced the country to confront how the law interprets intent, provocation, and proof. The explanation that the manslaughter plea was accepted because it would have been difficult to disprove provocation beyond reasonable doubt may be legally sound. But legality and public confidence are not always the same thing.

The case shocked many Jamaicans not only because of the outcome, but because of the timeline — a death first believed to be from natural causes before later findings changed the course of the investigation. For many women and families, these facts sit alongside deeper fears: If this can happen in a case with resources, visibility, and national attention, what happens in cases with none?

The argument that silence or delayed confession was about not wanting children to grow up without both parents has been particularly difficult for many to accept. The children have still lost their mother. And now they must also live with the lifelong emotional consequences of how she died. There is no scenario where violence against a mother protects her children.

When the justice system accepts manslaughter under provocation in intimate partner killings, it may be legally justified — but socially it raises hard questions. It risks reinforcing the perception that there are circumstances where lethal violence against women can be explained or mitigated.

The court’s decision exists within Jamaican law, where provocation can reduce a murder charge to manslaughter if intent cannot be proven. However, the broader social question remains: What message does this send to women who are already navigating fear inside relationships that are supposed to be safe?

Domestic femicide cannot be allowed to quietly settle into the background noise of national life. Not in our laws. Not in our language. Not in our collective conscience.

Justice must do more than meet a legal threshold — it must send an unmistakable signal about whose lives are protected without qualification. When outcomes create doubt about that protection, the damage spreads far beyond one courtroom or one family. It tells women to calculate risk inside their own homes. It tells children that violence can be explained away. It tells society that accountability has limits.

If women begin to believe that protection under the law is conditional, then we are not just failing victims — we are eroding the moral foundation of justice itself.

Jamaica cannot build safe families, safe communities, or a safe nation on fear inside the home.

Because when provocation becomes permission, we are not debating law anymore — we are deciding, in real time, whose lives are negotiable.

And a country that allows women to feel negotiable cannot call itself safe, just, or whole.

Comments